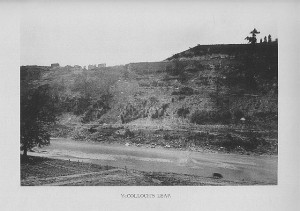

Major Samuel McColloch

In September 1777, during a Native American siege on Fort Henry, Major Samuel McColloch arrived at the fort with forty mounted men from Short Creek. The gates of the fort were thrown open to allow the men entrance. Major McColloch lingered behind to guide and protect the men. The Indians attacked, and all of the men except McColloch made it inside before they were forced to close the gates. McColloch found himself alone and surrounded by Native Americans, and he rode immediately towards the nearby hill in an attempt to escape. McColloch had earned a reputation as a very successful “borderer” (one who protected the frontier borders from the Native Americans) and was well known to both the frontiersmen and the Indians. The Indians eagerly pursued McColloch, and drove him to the summit of the hill.

As he rode along the top of the hill, he encountered another large body of Indians. He now found himself surrounded, with no path of escape. He knew that, because of his reputation and history against the Indians, he would be tortured and killed with great cruelty if he were to be captured alive. With all avenues of escape cut off, he turned and faced the precipice, and with the bridle in his left hand and his rifle in his right, he spurred his horse over the edge to an almost certain death. The hill at that location is about three hundred feet in height, and in many places is almost perpendicular.

The Indians rushed to the edge, expecting to see the Major lying dead in a crumpled heap at the bottom of the hill. To their great surprise they instead saw McColloch, still mounted on his white horse, galloping away from them.[1]

As legend of this famous “leap” became known, the place where it occurred became known as “McColloch’s Leap”. In 1917, the Daughters of the American Revolution placed a monument on the hill to commemorate McColloch’s bravery. The monument still stands near the top of Wheeling Hill, next to U.S. Route 40 (National Road).

BETTY ZANE

Elizabeth Zane, better known as “Betty Zane,” is hailed as a heroine of the Revolutionary War for her defense of Fort Henry in the wilderness of western Virginia. She was a sister of the famous Ebenezer Zane who founded Wheeling.

She was born near the Potomac River in Berkeley County, Virginia on July 19 — but the year is indefinite, with historians placing it between 1759 and 1766. In any case, Betty moved with her family at an early age to the area that now is Wheeling, West Virginia. The Zane family and a few others established Fort Henry in 1774.

Beyond that, their move was illegal, as the colonists were defying a royal order that reserved land west of the Appalachian Mountains for natives. The threat of attack increased as the American Revolution began back East: the tribes who lived beyond the Appalachians understandably wanted the British to put down the rebellion, and almost all of them allied themselves with the British.

Her family sent her to Philadelphia for some formal schooling, but Zane returned to Wheeling in 1781, the year that Americans won the important Battle of Yorktown. The war was not yet formally over though, and especially on the frontier, an alliance of British Canadians and Native Americans would continue to fight settlers until after the War of 1812.

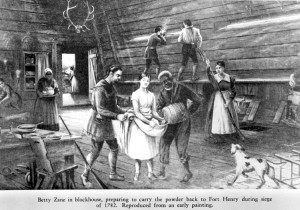

On September 11, 1782, Fort Henry was besieged by the British and their Native American allies. Betty Zane was among those trapped inside. The attackers greatly outnumbered the defenders: 250 Native American warriors allied with 50 exceptionally able British soldiers who never had been defeated. Inside Fort Henry, there were only about 20 males of fighting age. Worse, they soon found themselves running out of gunpowder.

Betty’s brother Ebenezer remembered that he had carelessly left a keg of gunpowder back at home. A few boys volunteered to retrieve it, but they were not allowed to leave because their deaths would mean the loss of valuable fighters. Knowing this, Betty volunteered to make the extremely perilous trip herself, claiming, “I am of no use here in the fort. I cannot fight, but I can bring the powder” (“The Heroine of Fort Henry”). She converted the usual disadvantage of being female into an advantage, as she reasoned that the British and Native Americans would be less inclined to shoot a girl than a boy. Her rationality combined with her daring spirit compelled her to brave the sixty yards between Fort Henry and the Zane home, knowing she faced some 300 enemies.

Luckily, she traveled to the Zane home unharmed. The Indians were amazed and yelled “Squaw, squaw” when she ran past. She wrapped the gunpowder in her apron and started to make her way back to Fort Henry. This time, however, the Native Americans and British were not fooled by the seemingly harmless girl, and they fired at her. Zane sprinted and miraculously managed to evade the gunfire, although one shot tore her dress. She successfully delivered the gunpowder, and two days later, the attackers retreated.

Not much is known about Betty Zane’s later life, but she married John McGloughlin and had five daughters. It was hard for widows to sustain their families on frontiers, and when John died, she married Jacob Clark and had two more children. She lived primarily in Martin’s Ferry, Ohio and died on August 23, 1823. She was buried in Walnut Grove Cemetery there, and a large statute honors her.

Two other girls in the fort, Molly Scott and Lydia Boggs, later claimed credit for this or similar feats, but most historians agree that Betty Zane’s role was key. Moreover, if Boggs and Scott do merit more recognition, it only reinforces the point that it was not unusual for young women to participate in the many conflicts of the new nation. The reality of violence on the frontier remained genuine for decades, and there was little chivalry for women; indeed, their risk increased because of the probability of rape if they were captured. Hundreds of girls and women were in fact taken captive, and many more were killed, often with horrific brutality.

Betty Zane’s cunning and bravery saved Fort Henry from seizure by the Native Americans and British. Her act of heroism furthered the Revolutionary cause, not only by protecting Fort Henry, but also by proving that girls contributed to it as well. Her bravery is immortalized in a book written by her descendant, the famous writer Zane Grey, entitled Betty Zane (1903). Her legacy lives on in the town of Betty Zane, West Virginia and also in Martin’s Ferry, where she is celebrated each year with “Betty Zane Pioneer Days.”